How Pop Mart’s Founder Turned Blind Boxes into a Billion-Dollar Empire

From Small-Town Underdog to China’s Toy Mogul: The Rise of Pop Mart and Its Billion-Dollar IP Empire

How a boy from a third-tier college created an emotional consumption giant that’s winning over global youth

In today’s middle-class social circles, Labubu—the quirky, goblin-like figure from Pop Mart—is fast becoming a bigger flex than luxury handbags. As one viral joke puts it: “An Hermès bag without Labubu isn’t true luxury.”

This odd yet lovable creature is now a staple of urban life, popping up in closets, on phone cases, car dashboards, and social media profiles. Behind Labubu’s cultural takeover stands Pop Mart, the brand that turned “emotional consumption” into a global business.

But perhaps the most surprising part of this story? Pop Mart wasn’t founded by a seasoned executive or an Ivy League graduate—but by Wang Ning, a young man from a small city in Henan, China, with no elite education, no industry background, and no funding. Just instinct, grit, and a deep understanding of what drives people to buy.

Humble Beginnings: A Kid from a County Town

Wang Ning grew up in Huojia County, Henan Province. His parents sold CDs, watches, and fishing gear from a local shop. From a young age, he learned how to “sell” by helping out at the family store, absorbing the local entrepreneurial spirit.

After the college entrance exam in 2005, while others relaxed, Wang organized a summer soccer camp. He wasn’t a top student and ended up at Sias International University of Zhengzhou, considered a third-tier college. To many, this might have seemed like a dead-end. For Wang, it was the launchpad of his dreams.

At college, he started a small production studio, selling 1,000 documentary-style DVDs about campus life in a single day. Soon after, he opened a “cubicle store” across from campus, renting mini shelves to display and sell lifestyle products—a business model inspired by Hong Kong’s LOG-ON stores.

These ventures laid the groundwork for Pop Mart, even if he didn’t know it yet.

Building Pop Mart from Scratch—Literally

With no design team or startup funds, Wang opened the first Pop Mart in Beijing’s tech hub Zhongguancun. He hand-painted the walls, hauled inventory, and even cleaned the store himself. Business was slow, and at one point, there were more employees than customers. Most investors passed. His team walked out. Wang almost gave up.

But one thing caught his eye: a mysterious spike in sales from a Japanese blind box toy called Sonny Angel, which made up nearly 30% of sales. He realized that people weren’t buying toys—they were buying emotional relief, comfort, and surprise.

So, Wang flew to Hong Kong and secured a licensing deal with artist Kenny Wong, bringing Molly, Pop Mart’s first original IP, to life. In 2016, the Molly Zodiac Series sold 80,000 units in 20 days, pulling in over 5 million RMB and turning the company profitable for the first time.

That was the beginning of an emotional business explosion.

Global Domination, One Blind Box at a Time

Over the next few years, Pop Mart signed 350+ artists worldwide, launching IPs like Dimoo, Skullpanda, and the now-iconic Labubu. The company turned toys into collectibles, retail into experience, and blind boxes into lifestyle statements.

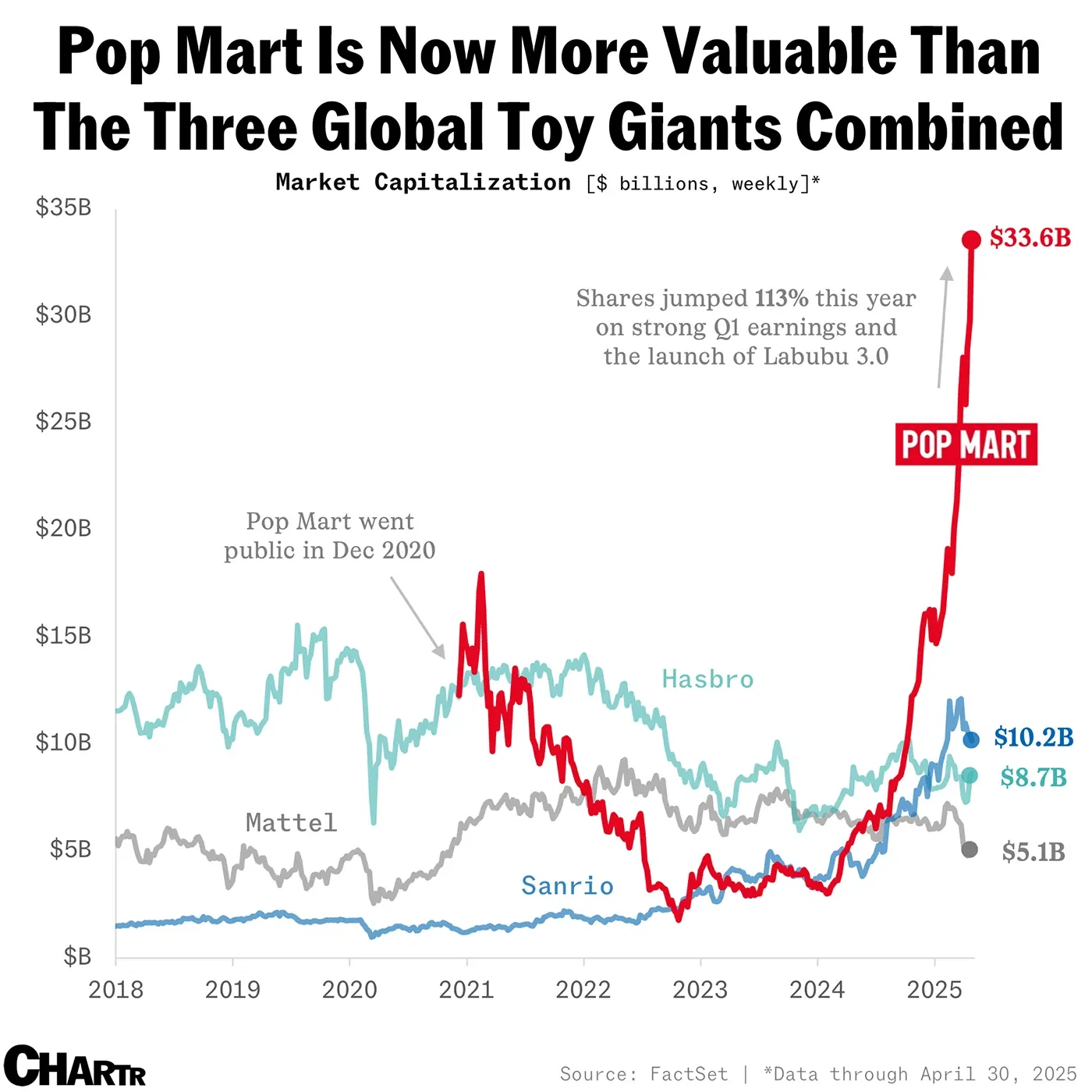

In 2020, Pop Mart went public on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, reaching a market cap of over HKD 100 billion. Wang Ning—the third-tier student once overlooked by elite investors—was now leading one of the most influential cultural brands in China.

Today, Pop Mart operates 500+ stores across nearly 100 countries. Its 2024 revenue hit 13 billion RMB, and its Hong Kong stock surged over 150% year-to-date, even amid a global slowdown.

Labubu has even charmed royalty and celebrities—Thailand’s princess shared her collection, and Rihanna was spotted carrying Labubu-adorned handbags during her pregnancy.

The Pop Mart Playbook: Intuition, Execution, and Emotional Value

Wang Ning often says he didn’t succeed because of talent—but because of timing, instinct, and action.

He wasn’t great at school—he even failed sociology. But while he struggled with theory, he was already practicing it in real life. From street stalls and DVD sales to pop-up stores and licensing deals, Wang’s entrepreneurial sense always kept him one step ahead.

As the company grew, he realized instinct wasn’t enough. From 2016 onward, Wang made a bold decision to focus only on designer toys, killing off non-core businesses to go all in on what no one else believed in at the time.

“Everyone has ideas,” he said. “But only those willing to stick with it for ten years will make something happen.”

Wang also later earned an MBA from Peking University’s Guanghua School of Management—proof that education matters, but action and experience matter more.

What Wang Ning’s Story Teaches Us

1. Start Early, Not Perfect

Wang’s edge was that he acted early—long before others found their paths. While his peers focused on grades, he built businesses and learned from real-world trials. His story reminds us that academic prestige isn’t everything. What matters is starting to build your judgment early.

2. Failure Is the Best Teacher

Pop Mart nearly collapsed—product flops, canceled IPs, and massive financial losses. But Wang didn’t give up. He pivoted, cut losses, restarted. His comeback wasn’t luck—it was the result of reflection and resilience. Young people should be allowed to fail—because the best learning often happens in the aftermath.

3. Real Education Is the Freedom to Try

Sias wasn’t an elite school, but it let students sell, organize, and create—an underrated blessing. True education gives space for mistakes and the freedom to experiment. That’s what nurtured Wang’s confidence and skills.

Parents and educators should recognize that hands-on experiences—not just grades—shape real growth. Let kids try, fail, and create.

Every Child Is a Blind Box of Potential

In his memoir Because I Am Unique, Wang reflects on how investors once dismissed him for lacking the “elite founder” profile. Years later, they admired his calm, rational temperament and consumer instincts.

Perhaps the very traits we overlook in children today are the ones that will power their success tomorrow.

Every child, like a blind box, holds surprises inside. You never know what brilliance is waiting to be discovered—until you give them a chance to open up.